Discuss the effectiveness of the flu vaccines including cost, prevention rate and at risk groups.

Introduction

Influenza is a disease of viral aetiology that circulates annually in temperate regions. Flu refers to a conglomerate of diseases, named with reference to their organismal source, for example swine flu, bird flu, or simply [human derived] flu Occasionally, viral strains active in animals infiltrate the human population and cause pandemic or epidemic infections (WHO 2017). The ‘flu season’ typically lasts for 4-6 weeks in the autumn and winter months, but its precise timing varies from year to year (Dexter et al. 2012). Acute symptoms include fatigue, arthralgia, myalgia, fever, sore throat, dry cough, headache, chills and loss of appetite (WHO 2017). People with general good health tend not to suffer with acute infections, but government institutions are concerned about the economic burden of flu due to stress on health services, work absenteeism and school closures in cases of probable pandemics (ibid., Dexter et al. 2012, Jackson et al. 2010, Smith et al. 2009).

The WHO recommends that vaccinations are used to mitigate the severity and spread of diseases following the development of the first vaccine in 1933 after viruses were identified as the causative agent of flu sickness (WHO 2017). In 1918, Spain suffered a very severe pandemic that still influences the global perception of flu as a very dangerous infection (Smith et al. 2009), an attitude that is leveraged by public health media campaigns to promote vaccination uptake (Rubin et al. 2010).

There are three influenza virus strain types: A, B and C. Vaccines are developed afresh yearly for types A and B based to best match the dangerous strains announced by the WHO each year. Type A viruses cause epidemic and pandemic infections in humans, B cause epidemic illness in humans, and C type do not pose a great enough risk to warrant developing a vaccine (WHO 2017). Live attenuated influenza vaccinations (LAIV) are whole virus vaccines administered intranasally and promote a more complex immune response, so are used in otherwise healthy children and adults but not elderly people or those with other risk factors (ibid.). Inactivated influenza vaccinations (IIV) are administered intramuscularly and are suitable for patients over 65 years of age and people considered at risk. The immunological community is working towards a universal vaccine that produces increased immunogenicity and would decrease the resources required for developing a new vaccine every year (de Boer et al. 2017).

What Determines Flu Vaccine Efficacy?

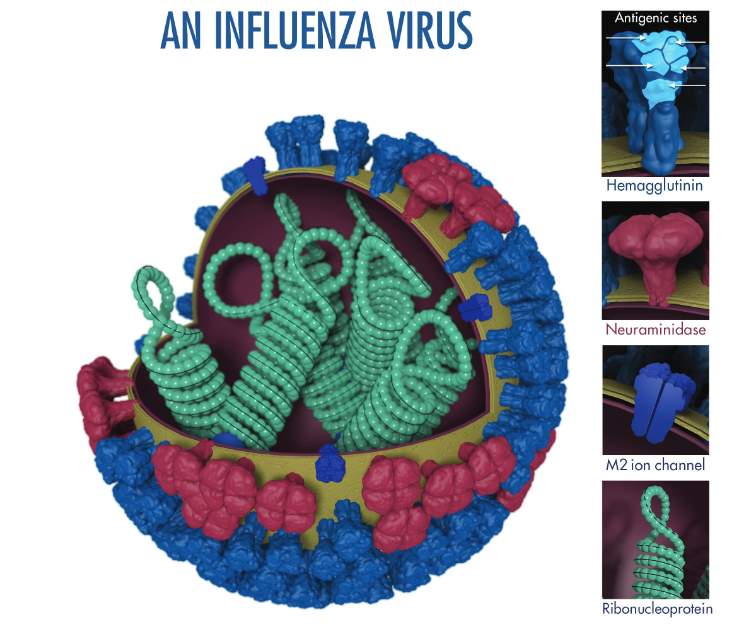

Influenza viruses belong to the Orthomyxoviridae family, and are covered in antigenic proteins, two of which determine their pathogenicity in humans. Hemagluttinin (HA) proteins are responsible for attaching viral particles to host cells. Their conformation alters by antigenic drift – viral mechanism of genetic transfer and adaptation – meaning that new vaccines that must be produced yearly. Neuraminidase (NA) is the protein responsible for releasing viral particles from the infected human cells that have served as incubators for their replication. When the human immune system develops immunity to NA as well as the novel HA, infection severity decreases (WHO 2017).

Figure 1: Molecular scale structure of influenza virus. Image from WHO (2017).

Vaccine efficacy is how the vaccine performs in ideal conditions and vaccine effectiveness (VE) is the performance in real life situations where conditions are far from ideal and controlled. Studies often use different end points to determine efficacy and VE, so the WHO has attempted to produce guidelines that standardise the data manipulation methodologies (WHO 2017).

The antigenic match between vaccine strains and the strains encountered in the environment, particularly of HA, is one of the primary determinants of vaccine efficacy and effectiveness, the values of which are poor when the vaccine is unmatched (Demicheli et al. 2018). The most effective, modelled vaccination campaigns are those administered twice to boost immunogenicity, and distributed to 60% of the population (Smith et al. 2009). It is relatively difficult to determine VE because mismatching causes massive variation in the data available (Public Health England 2016), so meta-analyses are useful sources of evidence. Public Health England (2016) quotes the meta-analysis generated figure of an overall VE of 59% in adults aged 18-65.

Are Flu Vaccines Cost-Effective?

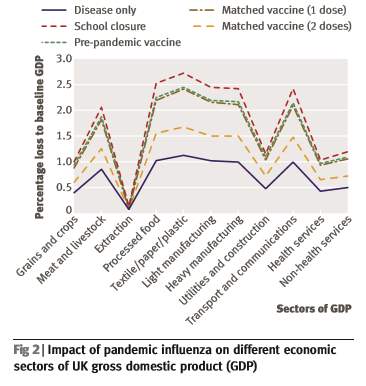

A 2010 paper (Smith et al.) cited the cost of vaccinating one British person at £16.60. This paper was written during the aftermath of the economic recession that began in 2008, and clearly argues that the cost of large scale vaccination is lower than the GDP loss of work absenteeism, school closure in pandemic seasons and behavioural changes to consumption that results from generation of fearful attitudes towards flu infections. The researchers noted that savings from vaccination are higher when the infection strain is more severe (ibid.), framing flu vaccination partly as an economic prophylaxis strategy for the wider health of the economy.

Figure 2: How flu influences GDP due to changes in consumption behaviours. Image from Smith et al., 2009.

Media and advertising campaigns launched by public health authorities are important determinants of the extent and type of behaviour change in which the public engages. For example, attitudes about the risk of swine flu in 2009 were shaped by media coverage such that people increased infection protection behaviours like buying disinfectant hand gels and tissues, but had the surprising effect of decreasing avoidant behaviours like using public transport (Rubin et al. 2010).

Public health authorities deem flu vaccination to be cost effective (Dexter et al. 2012). There are national and international targets of vaccination rates to reach which may pressure states to continue to dedicate vast resources – in the tens of billions of dollars (Doshi 2008) – to annual vaccination campaigns. Flu and influenza like illnesses (ILI) also significantly burden the health services, taking up beds and resources which might be avoided by vaccination. It may also be that pharmaceutical companies like the GlaxoSmithKline group and AstraZeneca that produce flu vaccines for the international market are significant economic players (Hawkes 2016, Jackson et al. 2010).

To What Extent do Flu Vaccines Prevent Flu Infection?

A Cochrane review of flu vaccination in the elderly concluded that for each person that avoids an influenza infection, 30 need to be vaccinated. Likewise, 42 people need to be vaccinated for every one person that avoids a case of ILI (Demicheli et al. 2018). Better matched vaccines are more successful at preventing flu infections, and vaccines are more effective at preventing infection in at risk groups (Public Health England 2016). However, an estimated 30-50% of influenza infections are asymptomatic (ibid.), making it difficult to report on prevention success with high accuracy.

Public health authorities are concerned about influenza related complications, such as secondary bacterial infections and more severe conditions like Guillain-Barre Syndrome, an autoimmune condition, the onset of which has previously been linked to organic flu infection and even one season’s vaccine in 1976 (WHO 2017). Because flu persists in the context of wider health ecologies, and an infection places stress on the immune system of the affected individual, flu vaccines may be effective in preventing otherwise dormant illnesses. These effects are clearly difficult to measure and have a speculative evidence element that is mobilised to shape public attitudes to the agenda of health governing bodies (Dexter et al. 2012, Rubin et al. 2010).

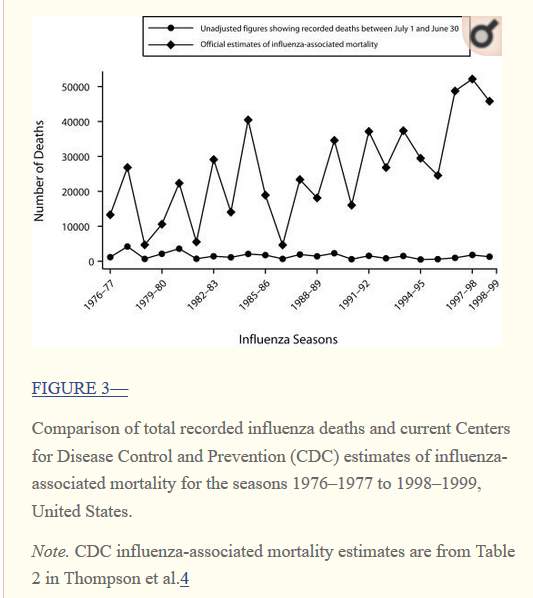

In the USA, report of deaths caused by influenza dropped from 10.2 per 100 000 people to 0.56 per 100 000 between the 1940s and 1990s (Doshi 2008), which may be reflective of similar trends across the western world. Similar epidemiological patterns are observed for other infectious diseases, indicating that socioecological factors such as urbanisation, quality of life, and general knowledge of hygiene may have intervened in the spread of viruses (ibid.). The difference between actual numbers of influenza related deaths and the estimates generated by national Centers for Disease Control may reflect a need to shape public perception to perceive flu as highly threatening in order to sustain flu vaccination uptake, as suggested in the graph below.

Figure 3: Graph from Doshi, 2008.

Are Flu Vaccines Effective in At-Risk Groups?

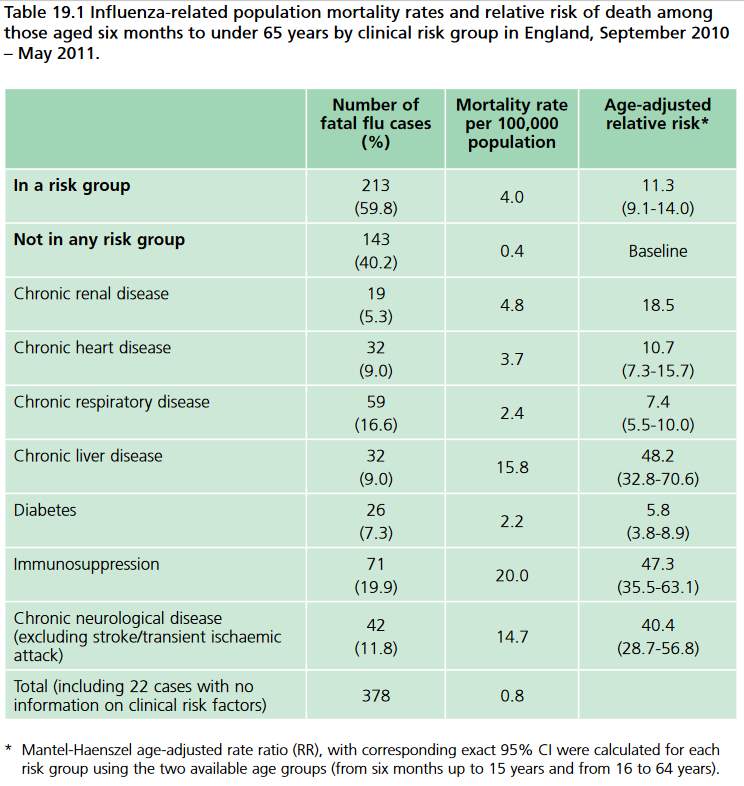

The UK aims to vaccinate 75% of people deemed at-risk to flu infection and subsequent complications (Dexter et al. 2012). High risk groups include people over 65, pregnant women, children under 6 months old, and people with existing chronic conditions such as kidney and liver disease, neurological disorders and conditions that lead to or require drug-mediated immunosuppression (Public Health England 2016). People in these high risk groups are considered more likely to suffer morbidity, mortality and complications from influenza and so are priority receivers of flu vaccines, which are free of charge to them in the UK (Dexter et al. 2012).

Vaccines are most effective in these people because the risk is higher, and it is considered worthwhile to vaccinate the entire population to some extent in order to diminish the risks to at-risk groups (Public Health England 2016). On the other hand, more care must be taken to ensure proper screening of individuals because IIV should be administered to high risk individuals, not LAIV because of the higher complexity of the immune response. The table below shows the influenza mortality rates of at risk groups relative to no risk groups.

Figure 4: Relative influenza related mortalities in at risk and no risk groups. Image from Public Health England, 2016.

Conclusion

Influenza vaccination is a worldwide, resource rich endeavour that requires a coordinated effort of viral surveillance, epidemiological research and reporting, seasonal provision of extra healthcare, public perception management and economic consideration. The organisational inertia of flu management means that bodies like the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (JCVI) is unlikely to claim that evidence shows that flu vaccination is no longer cost effective, and the trend is that more groups are offered vaccines, such as when children under 2 being offered LAIV from 2013 onwards (Kmietowicz 2013). The current vaccination regime is effective enough in terms of its prevention rate, protection of high risk groups from complications, and cost-benefit ratio that business will carry on as usual.

References

- de Boer, P., van Maanen, B., Damm, O., Ultsch, B., Dolk, F., Crépey, P., Pitman, R., Wilschut, J. and Postma, M. (2017). A systematic review of the health economic consequences of quadrivalent influenza vaccination. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 17(3), pp.249-265.

- Demicheli, V., Jefferson, T., Di Pietrantonj, C., Ferroni, E., Thorning, S., Thomas, R. and Rivetti, A. (2018). Vaccines for preventing influenza in the elderly. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews.

- Dexter, L., Teare, M., Dexter, M., Siriwardena, A. and Read, R. (2012). Strategies to increase influenza vaccination rates: outcomes of a nationwide cross-sectional survey of UK general practice. BMJ Open, 2(3), p.e000851.

- Doshi, P. (2008). Trends in Recorded Influenza Mortality: United States, 1900–2004. American Journal of Public Health, 98(5), pp.939-945.

- Hawkes, N. (2016). UK stands by nasal flu vaccine for children as US doctors are told to stop using it. BMJ, p.i3546.

- Kmietowicz, Z. (2013). Children in England to get flu vaccine at age 2 years from September. BMJ, 346(apr29 5), pp.f2792-f2792.

- Jackson LA, Gaglani MJ, Keyserling HL, Balser J, Bouveret N, Fries L, et al. (2010) Safety, efficacy, and immunogenicity of an inactivated influenza vaccine in healthy adults: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial over two influenza seasons. BMC Infectious Diseases. 10: 71.

- Public Health England (2016) Influenza in The Green Book.

- Rubin, G., Potts, H. and Michie, S. (2010). The impact of communications about swine flu (influenza A H1N1v) on public responses to the outbreak: results from 36 national telephone surveys in the UK. Health Technology Assessment, 14(34).

- Smith, R., Keogh-Brown, M., Barnett, T. and Tait, J. (2009). The economy-wide impact of pandemic influenza on the UK: a computable general equilibrium modelling experiment. BMJ, 339(nov19 1), pp.b4571-b4571.

- World Health Organization (2017). Module 23: Influenza Vaccines. The Immunological Basis for Immunization Series. [online] Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259211/9789241513050-eng.pdf?sequence=1 [Accessed 22 Oct. 2019].

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: