Appendix 2: Evidence Log of Learning Outcomes

|

Learning Outcomes |

Assignment – Evidence on page(s): |

|

1. Critically analyse key principles of assessment for Assistive Technology |

|

|

2. Analyse the process of assessment for Assistive Technology and measure the impact it has |

|

|

3. Critically evaluate issues around the use of Assistive Technology to support communication and learning |

|

|

4. Utilise theory for understanding good practice in the field of AT to support communication and learning |

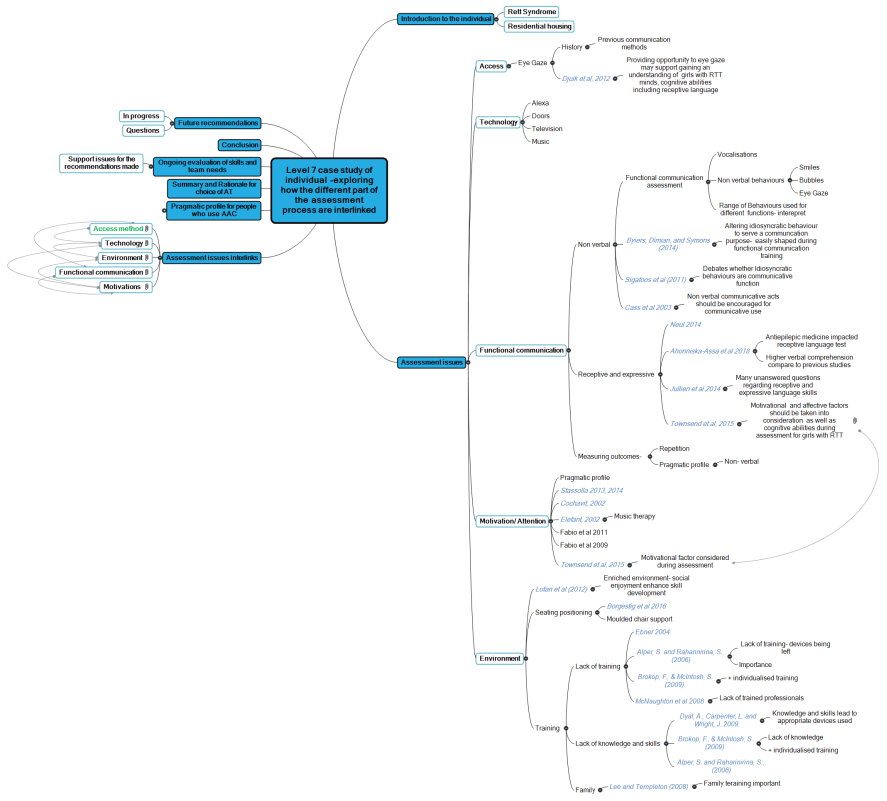

This assignment explores the clinical process of the assessment process of Assistive Technology (AT). AT definition in this essay comes from the World Health Organisation (WHO) (2001) which defines AT as “any product, instrument, equipment or improving functioning of a disabled person”. This assignment follows the assessment process of identifying the need for AT, determining the most appropriate device, implementing the device and then following up and evaluating the suitability for a 24 year old individual (M) with Rett Syndrome (RTT). Cook and Polgar (2014: PGNO, 2015:11) proposed a set of six principles: (1)assessment is “person centred” which considers all components of the Human Activity Assistive Technology (HAAT) model (2) the outcome is to enable participation in desired activities (3) an “evidence informed” process which interprets and gathers data (4) requires collaboration throughout with individual, key communication partners and professionals (5) process is carried out in an ethical manner (6) service is sustainable which includes ongoing evaluation and assessment.

RTT is a rare disease which is a neurological non-degenerative condition caused by mutation on the X-chromosome. There are two types of RTT, typical and atypical, and both impact individuals differently reinforcing the importance of ensuring the AT assessment is person centred. Neul et al. (2010) provide a revised diagnostic criteria for RTT to make it clarified and simplified as Neul et al commented that there was confusion regarding diagnosis of RTT. M case study supports this, as initially RTT was misdiagnosed. To support the diagnosis of RTT a frame of defined stages describing the progress of the disorder was introduced by Witt-Engerström and Hagberg (1990). Smeets, Pelc and Dan (2011) update and explain the four clinical stages. M is currently at stage four and appendix 1 shows pictures illustrating the different stages. The initial stage called “The Early-Onset Stagnation Period (Stage I)” (Smeets, Pelc and Dan, 2011:115) occurs between six months and one and ½ years old and during this time it has been noted that the girls demand little attention from their mothers also gross motor development is still progressing but with a delayed rate. Appendix 1 picture A shows M sitting for the first time independently at 10 months old. Typically this is a developmental milestone for a six to nine month baby. Enabling M to meet one of the exclusion criteria “grossly abnormal psychomotor development in the first six months of life” (Neul et al 2010:11) which is required for a diagnosis of typical RTT. This delay later was diagnosed as apraxia. Wilson (2013) describes apraxia as a difficulty to carry out planned motor movements including a limb movement and speech. In Bartalotta et al (2011) apraxia was perceived as the main limitation to communicate with others for girls with RTT due to the influence on consistency and speed of response and how others judge the cognitive skills. Therefore it is important when assessing M for AT that we take in to consideration the impact of the apraxia.

The second stage is “The Rapid Developmental Regression Period (Stage II)” (Smeets, Pelc and Dan, 2011:115) This stage is what led to the diagnosis for M. During this stage a rapid and specific regression of acquired abilities happens. This period of regression which is the main clinical requirement for a diagnosis of typical or classic RTT. Another aspect of the main criteria for RTT is the “partial or complete loss of acquired spoken language” (Neul et al 2010:11). M also provided evidence to meet this criteria as from speaking to parents it is understood M could count, name colours, objects, animals and letters. She was also able to express her need for the toilet and drink and explain how she was feeling. However, her parents noticed that speech started to disappear and M now has limited speech/vocalisations which have been evidence in the baseline functional communication assessment which was completed and carried out by the AT team around M. This included parents, house manager and support workers, community speech and language therapist and assistive technology officer. Appendix 2 shows the completed assessment. The data collected from the assessment demonstrated that M at this time M vocalises to attract attention, request an action or more, requests assistance and to show an opinion. This assessment supports two of the key principles during AT assessment as it gathered data which was then interpreted leading to an evidence performed process also required collaboration between individual, parents and professionals. Also the assessment provides evidence in identifying the need for AT to support M’s communication.

During regression M also lost purposeful hand movements and skills. Appendix 1 picture B shows M three years old arms extended playing in sandpit in stander and Appendix 1 picture C shows M creating a 3D picture independently picking up items but starting to require additional support to place items down. Appendix 1 picture D shows M still being able to sit independently at 6 years old. However Appendix 1 picture E shows M a year later at seven years old requiring full postural support in adapted chair and full support to hold spoon to feed. This picture also shows the prominent of the stereotypical hand movements of RTT identifying the progression to “The Pseudo-Stationary Stage (Stage III)” (Smeets, Pelc and Dan, 2011:116) during this time the stereotypical hand movements of RTT such as hand wringing and tapping became more prominent. These are both aspects of the main criteria for a diagnosis of typical RTT and both impact the ability to communicate with others. To reduce the frustration M showed during regression stage, her school started to introduce Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) which is a strategy where a picture/symbol is exchanged to another person for the item; this approach is based on the behaviourist B.F.Skinner’s approach to learning (PECS, nd). At this time research was showing the advantages of PECS for people with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) which are RTT got placed within ASD in previous Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. However in the recent revision RTT has been recognised as a spectrum disorder and it now stands independently (International Rett syndrome foundation, 2013). PECS was not successful for M due to the loss of purposeful hand movement and the stereotypical hand movements. This reinforces the importance of a person centred approach when assessing different communication methods. This has also been highlighted in different models when assessing AT. Cook and Hussey’s (1995 in Cook and Polgar, 2014) HAAT model emphasises the person carrying out an activity using AT to support participation similarly the Matching Person Technology (MPT) model (Schere and Glueckauf, 2005) also includes the same concepts as the HATT model but the MPT assessment is based around person centred goals designed to identify AT most likely to be implemented by the person. Whereas the HAAT model explores specific activities which has been proposed as a key principle when carrying out AT Assessment as the AT should enable individual to participate in desired activities and tasks.

Additionally to the main criteria related to a diagnosis of RTT there is also supportive criteria which are not required but are often present. When looking at the supportive criteria M has developed several of these including “breathing disturbances when awake”, “intense eye communication” and “scoliosis” (Neul et al 2010:11). M scoliosis was diagnosed during stage four “Late Motor Deterioration” (Smeets, Pelc and Dan, 2011:116) Appendix 1 picture F shows M at 12 years in a supported chair with chest restraints at the beginning of scoliosis to Appendix 1 picture G M now aged 24 years old in a personalised moulded chair to reduce the speed of development of scoliosis curve.

All symptoms identified (apraxia, regression, stereotypical hand movements, breathing disturbances and scoliosis) have potential to impact M’s ability to communicate therefore reinforcing the need for the AT assessment to support M’s communication and ensuring the assessment is person centred through observing how each symptom impacts M’s communication personally. M’s parents explained during her time in education M had sporadic opportunities to use Eye Gaze device due to the intense eye communication M presented. Appendix 3 shows photo of M trialling eye gaze computer at 12 years old. The history of RTT and eye gaze shows that the founder of RTT Dr Andreas Rett saw eye gaze potential in girls with RTT by stating “their eyes are talking to them. I’m sure the girls understand everything, but they can do nothing with the information” (Hunter, 2007). More recently, Townsend et al. (2018) have been able to provide scientific evidence that the oculmotor pathway is not affected by RTT making it a reliable method by which an individual can communicate using eye pointing and eye gaze technology. Therefore during the assessment M. will be provided opportunity to trial eye gaze device.

Furthermore M also has a diagnosis of epilepsy. In Bartolotta (2014) study it was reported that seizure activity could impact the quality of responsiveness for a person with RTT therefore it is important for observations to be repeated as the individuals performance could vary. This supports Woodyatt, Marinac, Darnell, Sigafoos, & Halle (2004) who observed that after seizure activity girls with RTT may not be fully engaged in communication interactions therefore it is important that support staff provide time and opportunities to follow up interactions during the day. This has been evidenced in sessions with M as during an afternoon session M didn’t seem as engaged in the interaction with the eye gaze device and kept placing herself onto the rest button which pauses the eye gaze device. During this session I was then informed that earlier in the day M had had a seizure. Adult asked M if she wanted to stop (modelling stop) M then looked at adult. Therefore M used her non-verbal communication even though technology was available to ask for the session to stop. Bartolotta (2014) supports this as explains due to the range of responsiveness professionals are recommended to use a range of modalities to assess communication skills, within the study each participant used on average three different methods this included eye gaze, body movements and paper based communication systems to communicate. Therefore highlighting the importance to observe M’s non-verbal communication skills to confirm choice which were observed during a baseline functional communication assessment (gazing, smiling, vocalisation and body movement) which are used simultaneously for different communicative functions. However, Sigafoos et al. (2011) debates whether these informal idiosyncratic behaviours are a communicative function. Previous research by Cass et al. (2003) argues that these verbal communicative acts should be encouraged for communicative use and should be interpreted consistently to motivate M to communicate further. Therefore a target set during the AT assessment was to provide further opportunities for M to develop her non- verbal communication skills for yes/ no, like/ dislike. To support this staff and family have since received training in regards to interpreting M non-verbal communication skills consistently and it has been recognised that M’s yes (looking at adult) and no (looking away) reactions are becoming more consistent across a range of communication partners.

This has led to further assessment questions in understanding M’s cognitive and communicative skills. Sigafoos et al ( 2009) support this and suggest a thorough communication assessment should be completed first to identify priorities and intervention requirements. To gain further understanding of M current pragmatic functions a Pragmatic Profile for People who use AAC was completed Appendix 4 shows the summary sheet alongside this and the qualitative data collected it highlighted potential areas for targets to be developed. This assessment supports two of the key principles during AT assessment as it gathered data which was then interpreted leading to evidence informed process also required collaboration between individual, parents and professionals. However it has been recognised that assessing cognitive and communication abilities through standard assessment methods is not possible for individuals with RTT and therefore a balance observational and standardised measures are required when assessing girls with RTT (Sigafoos et al 2011). Bartollotta et al (2011) supports this as says assessing intentional communication for people with severe difficulties is complex. This has historically contributed to the belief that these individuals are severely cognitively impaired with little or no intentional communication ability. However, parents and primary carers of M believe she uses eye contact to express communication and that she understands more than she can express. Djukic et al (2012) explored non-verbal communication ability with visual preferences and social preferences and found that the participants exhibited a preference for socially weighted stimuli. Providing evidence to suggest that the girls have good joint attention and eye contact with people indicating of the possibility that they have a desire and intent to communicate therefore validating data from parent’s perspective and previous research from Cass et al (2003) and further more Hetzroni and Rubin (2006) provide evidence to suggest that the joint attention can be taught and developed to people with RTT. M has shown evidence of developing her joint attention when using her eye gaze device as has started to use device to communicate her needs leading to less frustration M initially showed.

Previously Baptista et al (2006) researched whether girls with RTT could use eye gaze intentionally by observing their performance in three cognitive tasks. 6 out of 7 respond correctly to verbal instructions and the similar results found in the semantic categorisation task. During each task participant were exposed to each item for 5 seconds and in comparison Velloso, Araújo and Schwartzman (2009) also assessed visual tracking and looked at educational concepts (colour and shapes) and found different results as participants had more incorrect answers than correct but the boards were only displayed for 3 or 4 seconds depending on task. This paper however commented that a limitation of the study was the limit in the amount of time the boards were on offer but recognised a gap in research looking at what the waiting time should be. Therefore providing evidence to suggest when assessing M for AT it is important to be aware on the amount of waiting time provided when assessing M’s cognitive and communication skills also supporting the principle of AT assessment of ensuring the assessment is person centred to the time M requires also completed in an ethical manner so the session are non-maleficence so stopping session when M selects stop also giving M time to process when places herself on rest.

More recent studies have explored benefits of using Eye gaze technology when assessing individuals with RTT receptive and cognitive language suggesting some individuals with RTT may be operating on a cognitive par with the neurotypical peers (Ahonniska-Assa et al, 2018; Clarkson et al, 2017). Clarkson et al (2017) found better performance on visual reception and receptive task when adapted to support use of eye gaze device. This supports Burkhart and Wine’s (2010) clinical reports that suggest individuals with RTT who have access to aided communication have a higher linguistic and communicative level reinforcing the need for AT for M so a communicative level can be assessed to ensure that the correct vocabulary and size of grid set can be established.

This led to further assessment questions relating to M’s motivations for communication. Several studies have explored the impact motivation has on communication for people with a range of disabilities. Lotan (2007) provide evidence to support having an enriched environment which is person centred and provides social enjoyment has the potential to enhance physical skill development in girls with RTT. Similarly, Townsend et al. (2015) explains to assess girls with RTT cognitive abilities effectively through the implementation of AT a thorough assessment considering the motivational and affective factors is required supporting assessment question in relation to M’s motivations and the need for the AT assessment to be person centred as demonstrated in the HAAT model also having activities which are person centred to develop participation. Stasolla et al (2014) found using a child centred practice and goals which are highly motivating encourage children with RTT to become more engaged therefore supporting their skill development. To develop a greater understanding of M.’s motivations a Talking Mat which is an interactive resource used to support people with disabilities expressing their feelings (Talking Mats, 2013). Appendix 5 Picture A shows an image of completed Talking Mat. From completing the Talking Mat with M it allowed further understanding of where she would like use her eye gaze and what she would like to use her eye gaze device for therefore allowing an evidence informed process to take place when organising vocabulary on her grid set. A key principle of AT assessment highlighted by Cook and Polgar (2014, 2015). Since completing the Talking Mat the environmental control folder has moved to the top of the core topics allowing easier access to Alexa, television and art programme. Appendix 5 Picture B shows an image of M current home grid page.

When assessing M there are a number of external barriers which could impact the implementation of AT to support M’s communication and learning. Early childhood theorists in particular Lev Vygotsky and social learning theories have researched how the social environment impacts development of communication and learning (Beloglovsky and Daly, 2015). Therefore it is important M has access to eye gaze device to enable opportunities to interact with environmental controls, other residents, support staff and family. Rackensberg et al (2005) also highlighted the importance of providing opportunities for individual exploration. Individuals who use AT commented in this study that the lack of individual exploration contributed to slower learning of device and software therefore it is important that M is provided regular opportunities to individually explore and be model to enable effective implementation of AT. This is interlinked with time which has been recognised as a barrier Binginlas (2009) literature review provided evidence to support this is found the amount of implementation of AT within an environment could be linked to the lack of time. Therefore it is important that staff at M’s Day Centre, residential house and family are trained and supported to use device to enable further opportunities for M to use AT. Sharpe (2010) argues that support and training are greater barriers than lack of trust time when implementing AT within settings. Baxter et al. (2012) supports this has provided evidence to suggest a link between confidence in using device and increased implementation and access to device. Loncke (2014) supports this in his framework for successful implementation as highlighted four main areas which impact implementation these include communication and ease of use of device and software. More recently Borgestig et al. (2017) provided evidence to support this has found devices which had been designed and personalised alongside the user and ongoing support has been provided increases the usage and performance. Reinforcing a key principle of the AT assessment of ensuring the process is person centred. Similarly it is important that professionals, family and support staff work collaboratively throughout the assessment and implementation to ensure effective implementation of AT for M. Rackensberg et al (2005) provided evidence to suggest that lack of support and training throughout the process led to abandonment of device. Borgestig et al. (2017) found devices not being used to full potential within the first three months due to lack of ongoing support in implementing device. This supports findings found when data of usage of M device was collected and analysed prior and after initial training within the setting. Appendix 6 shows a line graph illustrating the total active usage time weekly on grid three prior to training on the 24th and after showing the increase of active usage of device the week after training then decreasing when support was not available and then increasing one support was back in place highlighting the need for ongoing support in implementing AT.

Next steps

Reference List

- Ahonniska-Assa, J., Polack, O., Saraf, E., Wine, J., Silberg, T., Nissenkorn, A. and Ben-Zeev, B., 2018. Assessing cognitive functioning in females with Rett syndrome by eye-tracking methodology. european journal of paediatric neurology, 22(1), pp.39-45.

- Baptista, P.M., Mercadante, M.T., Macedo, E.C. and Schwartzman, J.S., 2006. Cognitive performance in Rett syndrome girls: a pilot study using eyetracking technology. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 50(9), pp.662-666.Bartolotta, T., 2014. Communication skills in girls with Rett syndrome. In Comprehensive Guide to Autism (pp. 2689-2709). Springer, New York, NY.

- Burkhart, L. and Wine, J. (2010) Rett Syndrome Apraxia and Communication. ISAAC Barcelona. [Online] [Accessed on 12th November 2018] http://lindaburkhart.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/Rett_Linda_Judy_ISAAC_7_10_hand.pdf.

- Cass, H., Reilly, S., Owen, L., Wisbeach, A., Weekes, L., Slonims, V., Wigram, T. and Charman, T., 2003. Findings from a multidisciplinary clinical case series of females with Rett syndrome. Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology, 45(5), pp.325-337.

- Clarkson, T., LeBlanc, J., DeGregorio, G., Vogel-Farley, V., Barnes, K., Kaufmann, W.E. and Nelson, C.A., 2017. Adapting the Mullen Scales of Early Learning for a Standardized Measure of Development in Children With Rett Syndrome. Intellectual and developmental disabilities, 55(6), pp.419-431.

- Cook, A.M. and Polgar, J.M., 2014. Assistive Technologies-E-Book: Principles and Practice. Elsevier Health Sciences.

- Djukic, A., McDermott, M.V., Mavrommatis, K. and Martins, C.L., 2012. Rett syndrome: Basic features of visual processing—A pilot study of eye-tracking. Pediatric neurology, 47(1), pp.25-29.

- Hetzroni, O.E. and Rubin, C., 2006. Identifying patterns of communicative behaviors in girls with Rett syndrome. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 22(1), pp.48-61.

- Hunter,K. (2012) The Rett Syndrome Handbook. 2nd ed., Clinton: IRSA Publishing. [Online][Accessed on 12th November 2018] https://www.rettsyndrome.org/document.doc?id=35.

- (International Rett Syndrome Foundation, 2013) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5.0) Released May 22 Signifies Change for Rett Syndrome. [Online] [Accessed on 13th November 2018] https://www.rettsyndrome.org/doent.doc?id=130.

- Lotan, M., 2007. Assistive technology and supplementary treatment for individuals with Rett syndrome. The Scientific World Journal, 7, pp.903-948.

- Neul, J.L., Kaufmann, W.E., Glaze, D.G., Christodoulou, J., Clarke, A.J., Bahi‐Buisson, N., Leonard, H., Bailey, M.E., Schanen, N.C., Zappella, M. and Renieri, A., 2010. Rett syndrome: revised diagnostic criteria and nomenclature. Annals of neurology, 68(6), pp.944-950.

- (PECS, nd).

- Scherer, M.J. and Glueckauf, R., 2005. Assessing the benefits of assistive technologies for activities and participation. Rehabilitation Psychology, 50(2), p.132.

- Sigafoos, J., Green, V.A., Schlosser, R., O’eilly, M.F., Lancioni, G.E., Rispoli, M. and Lang, R., 2009. Communication intervention in Rett syndrome: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 3(2), pp.304-318.

- Sigafoos, J., Kagohara, D., van der Meer, L., Green, V.A., O’Reilly, M.F., Lancioni, G.E., Lang, R., Rispoli, M. and Zisimopoulos, D., 2011. Communication assessment for individuals with Rett syndrome: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 5(2), pp.692-700.

- Smeets, E.E.J., Pelc, K. and Dan, B., 2011. Rett syndrome. Molecular syndromology, 2(3-5), pp.113-127.

- Stasolla, F., De Pace, C., Damiani, R., Di Leone, A., Albano, V. and Perilli, V., 2014. Comparing PECS and VOCA to promote communication opportunities and to reduce stereotyped behaviors by three girls with Rett syndrome. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 8(10), pp.1269-1278.

- Townend, G.S., van de Berg, R., de Breet, L.H., Hiemstra, M., Wagter, L., Smeets, E., Widdershoven, J., Kingma, H. and Curfs, L.M., 2018. Oculomotor Function in Individuals With Rett Syndrome. Pediatric neurology, 88, pp.48-58.

- Velloso, R.D.L., Araújo, C.A.D. and Schwartzman, J.S., 2009. Concepts of color, shape, size and position in ten children with Rett syndrome. Arquivos de neuro-psiquiatria, 67(1), pp.50-54.Wilson (2013)

- Witt-Engerström, I. and Hagberg, B., 1990. The Rett syndrome: gross motor disability and neural impairment in adults. Brain and Development, 12(1), pp.23-26.

- Woodyatt, G., Marinac, J., Darnell, R., Sigafoos, J. and Halle, J., 2004. Behaviour state analysis in Rett syndrome: Continuous data reliability measurement. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 51(4), pp.383-400.

Appendix

Communication Function Assessment (Adapted from Pragmatics Profile Summers et al)

Name of client: M. Date: 27/9/18

Completed by: Community Speech and Language Therapist, home manager, assistive technology officer

|

Pragmatic |

Function Not observed |

Vocalisations |

Gesture/ whole body movement |

Speech |

PECS/ Sign/ Symbol |

iPad/ device |

|

Attracts attention

|

/- high pitched vocalisation |

|||||

|

Directs attention events/ people/ Objects “GO.. |

/ |

|||||

|

Requests an object

|

/ |

/ |

||||

|

Requests an action

|

/ Interpret as a request |

/ eye contact for yes |

||||

|

Requests for more or re-occurrence |

/ vocalise eg if film stops |

|||||

|

Requests assistance

|

/ vocalise |

|||||

|

Rejects/ protests

|

/ eg not open mouth for drink |

|||||

|

Accepting

|

/ smile and eye contact |

|||||

|

Greetings

|

/ looks up at adult |

|||||

|

Asserts independence

|

/ |

|||||

|

Gives an opinion like/ don’t like |

/- if don’t like |

Rolls eyes Won’t engage |

Working towards introducing commenting words |

|||

|

Naming/ labelling |

/ |

|||||

|

Comments on object |

/ |

|||||

|

Answers question |

/ smile, eye contact looking away for no |

|||||

|

Ask question |

/ |

|||||

|

Express emotion |

/ vocalisations |

/ facial expression/ body language |

||||

|

Share information |

/ |

Vocalisations: longer / more sustained, louder- more distressed

Limited means for a range of functions

Cite This Work

To export a reference to this article please select a referencing style below: